Though official records are unsurprisingly spotty for people born into slavery, historians are pretty sure Harriet Tubman's birth year was 1822.

The future Underground Railroad conductor grew up amid the forests, marshes, and waterways of Maryland's Dorchester County—a landscape that would play a crucial role in Tubman's life. After all, her familiarity with the setting and formidable outdoor know-how would prove useful during her own escape to freedom in 1849 as well as in the 13 missions she subsequently led back to Maryland to rescue dozens of other enslaved African Americans in the decade before the Civil War.

That wasn't the end of Tubman's heroics—during the war, she would serve as a Union Army scout and spy, eventually becoming the first woman in U.S. history to lead an armed military raid—and she would continue fighting for civil rights, women's suffrage, and better care for the elderly until her death in 1913.

But the Eastern Shore of Maryland is where Tubman's story began and where its most celebrated chapters unfolded. Modern-day travelers can follow along on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, a 125-mile, self-guided driving tour that connects more than 40 historically significant sites in Maryland's Dorchester and Caroline Counties before continuing into Delaware and ending in Philadelphia.

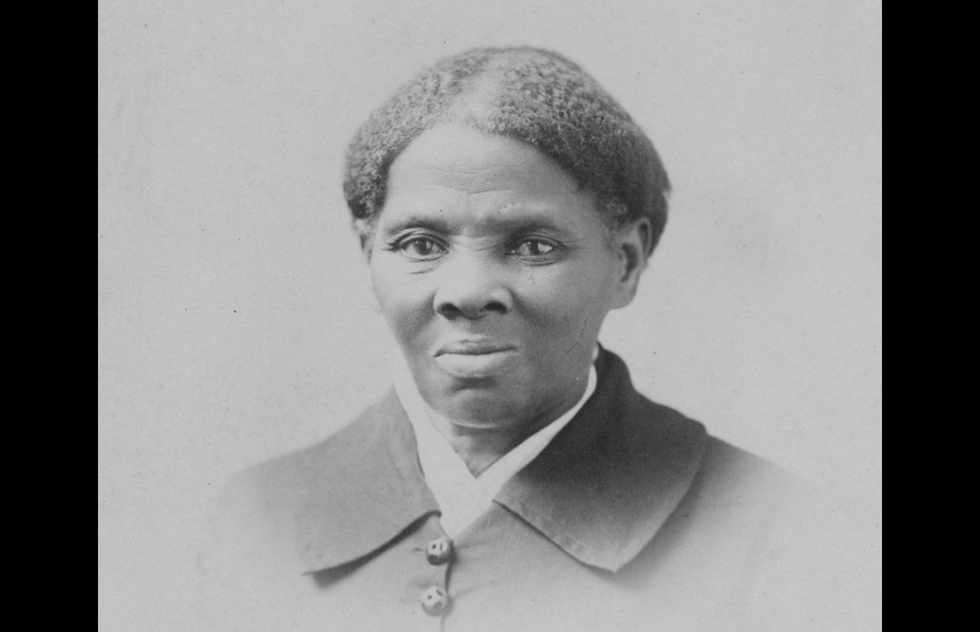

(Undated portrait of Harriet Tubman; public domain)

(Undated portrait of Harriet Tubman; public domain)

To take the road trip—whether in part or in full—consult the online interactive map, free driving instructions, and evocative audio guide from the byway's official website. (There are also plenty of guided tours from independent operators if you're not the DIY type.)

Below, we've gathered six of the route's must-see Tubman sites in Maryland's Eastern Shore region along with some ideas for further explorations.

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center

(Credit: F Delventhal / Flickr | Bohemian Baltimore [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

(Credit: F Delventhal / Flickr | Bohemian Baltimore [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

A good place to start a Tubman tour is at this Church Creek facility surrounded by lands preserved by the National Park Service and Maryland State Parks. Inside, multimedia exhibits use photos, video, and bronzed dioramas to recount Tubman's life story, her courageous escape to freedom, and her rescue missions with the Underground Railroad. Visitors get a sense of just how daring the operators of that clandestine network of secret routes and safe houses were, leading freedom seekers through inhospitable country in the dead of night with only the North Star as a navigational tool.

Displays also cover Tubman's achievements during the Civil War and her later years as a suffragist and human rights activist. Throughout, the focus remains, as in Tubman's life, on the transformative possibilities of freedom and why it is worth fighting for.

As Tubman recalled of entering Pennsylvania for the first time (according to her first biographer, Sarah H. Bradford), “When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge

(Credit: Francine K. Rattner / Shutterstock)

(Credit: Francine K. Rattner / Shutterstock)

Adjacent to the visitor center, the 30,000 acres of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge remain virtually the same as when Tubman worked on farms here, checking muskrat traps, hauling logs, and doing other difficult tasks that would make her closely acquainted with the terrain. As reported in the Baltimore Sun, archaeologists announced in 2021 that they discovered the homesite of Tubman's father, Ben Ross, within the boundaries of the refuge.

Now a preserve for waterfowl, the refuge has hiking trails and paddling routes showing off the woods, sloughs, fields, and creeks Tubman lived and labored among in her early years.

Brodess Farm

(Credit: Lorie Shaull / Flickr)

(Credit: Lorie Shaull / Flickr)

No trace remains of the original farmhouse on Greenbrier Road (about 5.5 miles east of the visitor center) where Tubman's enslaver, Edward Brodess, lived. He moved Tubman's mother, Rit, and her children to the farm shortly after Harriet's birth, but frequently hired the family members out to other landowners in the area.

According to Kate Clifford Larson's 2003 biography, Tubman later said in an interview that Brodess wasn't "unnecessarily cruel," but some of the other slaveholders to whom he temporarily sent Tubman and her siblings proved to be "tyrannical and brutal."

Tubman's brothers Robert and Ben would describe the Brodesses as plenty cruel, however. "Where I came from, it would make your flesh creep, and your hair stand on end, to know what they do to the slaves," said Ben.

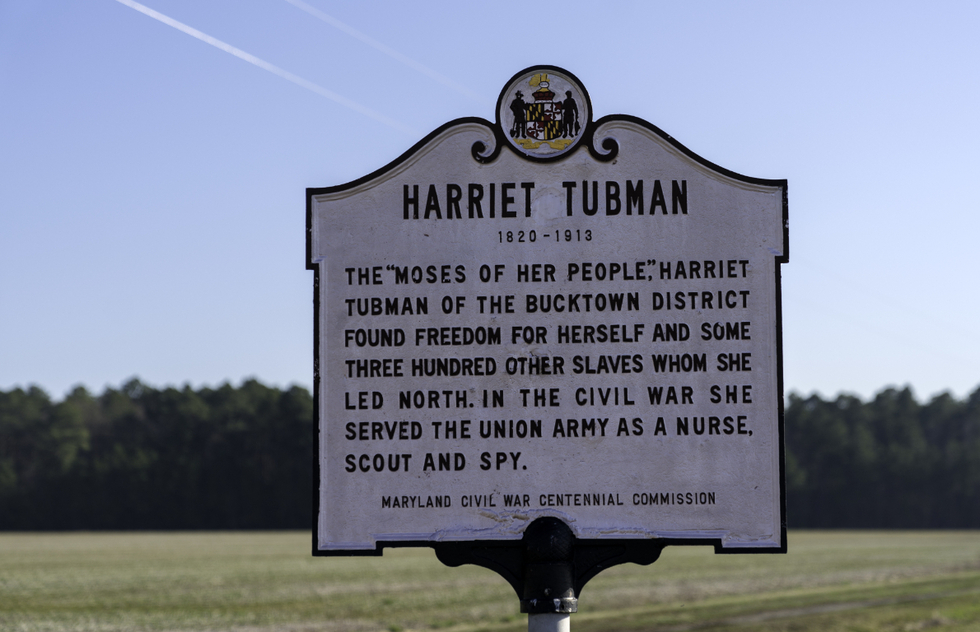

Today, the land is still privately owned, but there's a small roadside pull-off with a historical marker and interpretative panel explaining Tubman's link to the property.

Bucktown General Store

(Credit: Mobilus In Mobili / Flickr)

(Credit: Mobilus In Mobili / Flickr)

Just about a mile east of the Brodess site you'll find the small country store where Tubman received the head injury that nearly killed her when she was a young adolescent. It happened when an overseer threw a 2-pound weight at an enslaved man who was trying to run away. The weight hit Tubman instead, and she had headaches, seizures, and visions for the rest of her life.

Check in advance to see whether the store's re-created interior is open for tours.

Harriet Tubman Museum and Educational Center

Continue on the Tubman Byway about 10 miles north to reach the town of Cambridge. The Dorchester County seat contains several sites connected to the region's slaveholding past, including Long Wharf Park, where kidnapped Africans were sold into slavery along the waterfront, and the Dorchester County Courthouse, where one of Tubman's nieces escaped from the auction block.

Cambridge's community-led Harriet Tubman Museum commemorates its namesake with historical exhibits, regional tours, special events such as jazz concerts, and displays of artworks including quilts and paintings. The institution's most striking piece is on the building's exterior. Completed by artist Michael Rosato in 2019, a mural entitled "Take My Hand" (pictured at the top of this page) depicts Tubman reaching toward the viewer against a backdrop of Eastern Shore wetlands.

Harriet Tubman Memorial Garden

(Credit: F Delventhal / Flickr)

(Credit: F Delventhal / Flickr)

One last stop before you leave Cambridge should be made at the roadside garden (at Route 50 and Washington St.) decorated with murals painted by Charles Ross, a descendant of Tubman. It's a reminder that the abolitionist still has relatives in the area—and that her legacy of pursuing freedom with courage and compassion remains as vital as ever.

If you opt to stay on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, you'll eventually come to other illuminating sites such as Caroline County's Webb Cabin, where you can see the typical home of a free Black farmer in the 1850s; the nearby Tuckahoe Neck Quaker Meeting House, which was used as a way station on the Underground Railroad; and several noteworthy bridges, creeks, and crossings involved in Tubman's heroic rescue missions.

To learn more about Harriet Tubman's later years, you can visit the national historical park dedicated to her in Auburn, New York. Tubman lived in that Finger Lakes town—appropriately close to the feminist haven of Seneca Falls—for more than half a century starting in 1859.

The park encompasses, among other attractions, her red-brick residence and farmland, the church she attended, and the (rebuilt) nursing home she started for Black seniors not long before her death in 1913 at age 91 (give or take).